Imagine, if you will, the Roman Empire at its height. The Emperor didn’t wake up and fret over the exact angle a legionnaire should hold a shovel to dig a trench. He simply pointed at a map and declared, “I want a wall here to keep the barbarians out”. He expressed the “What” (a wall) and left the messy, back-breaking “How” (the stones, the sweat, and the engineering) to someone else.

In the world of computing, we call this Declarative Programming. And while we currently act like talking to an AI to build an app is a shiny new miracle, we’ve actually been trying to play “Emperor” with our computers for over fifty years.

The Dark Ages of Procedural Peasantry

Before the 1970s, programmers were less like emperors and more like weary kitchen staff following a recipe that required them to explain how to breathe while chopping onions. If you wanted a simple business report in COBOL, you had to write twelve pages of dense code. You had to tell the computer how to open a file, how to look at every single record one-by-one, how to handle errors, and finally—exhaustingly—how to close the file.

It was slow, expensive, and frankly, a bit of a buzzkill for business growth.

The Great Hope: Enter the 4GLs

In the early 80s, a “Great Hope” arrived: Fourth-Generation Languages (4GLs). The promise was intoxicatingly simple: “Application Development Without Programmers” (codified by James Martin in his influential 1981 book). We were told that business analysts—the people who actually understood the business—could finally shove the “highly trained specialists” aside and “talk” directly to the machines.

I lived through this “Renaissance.” While the world was marveling at the first minicomputers from DEC and Data General (where I did a ton of assembly programming) and PCs, I was on the front lines of the mainframe world using tools like FOCUS and CA-TELLAGRAF.

- FOCUS was like magic. Instead of twelve pages of COBOL, you could write a single, readable statement to get your data. You just declared what data you wanted, and the system’s “implicit loop” did the heavy lifting.

- CA-TELLAGRAF brought this philosophy to pictures. Instead of math-heavy vector coordinates, you’d simply tell the machine: “make the x-axis 6 inches long”.

It was a beautiful dream. We were democratizing the digital world! We were insulating our precious business logic from the cold, hard “hardware” underneath.

The Cycle of Rebranding

The initial, undeniable success of 4GLs in data retrieval and reporting fostered a much broader and more ambitious vision within the IT industry: if declarative statements could generate reports, could they not be utilized to generate entire enterprise software systems? Over the following decades, this same “Emperor’s Dream” kept returning under fancy new names, like a classic movie that gets a mediocre reboot every ten years.

- CASE (Computer-Aided Software Engineering): The 90s attempted to draw a few diagrams and have a “black box” spit out a whole system overnight.

- MDA (Model-Driven Architecture): The 2000s quest to create “Platform-Independent Models” that would supposedly last forever, even if the underlying tech changed.

- DSLs (Domain Specific Languages): Specialized “micro-languages” for specific tasks.

Hover over or tap a timeline epoch above to explore its specific productivity promise and historical context.

The Evolution of Declarative Enterprise Abstractions

The Productivity Paradox and the “What vs. How” Movement

The primary value proposition of 4GLs and subsequent declarative abstraction layers has always been to enhance enterprise productivity. By shifting the focus from low-level mechanical coding to high-level business logic, these technologies promised to drastically reduce development

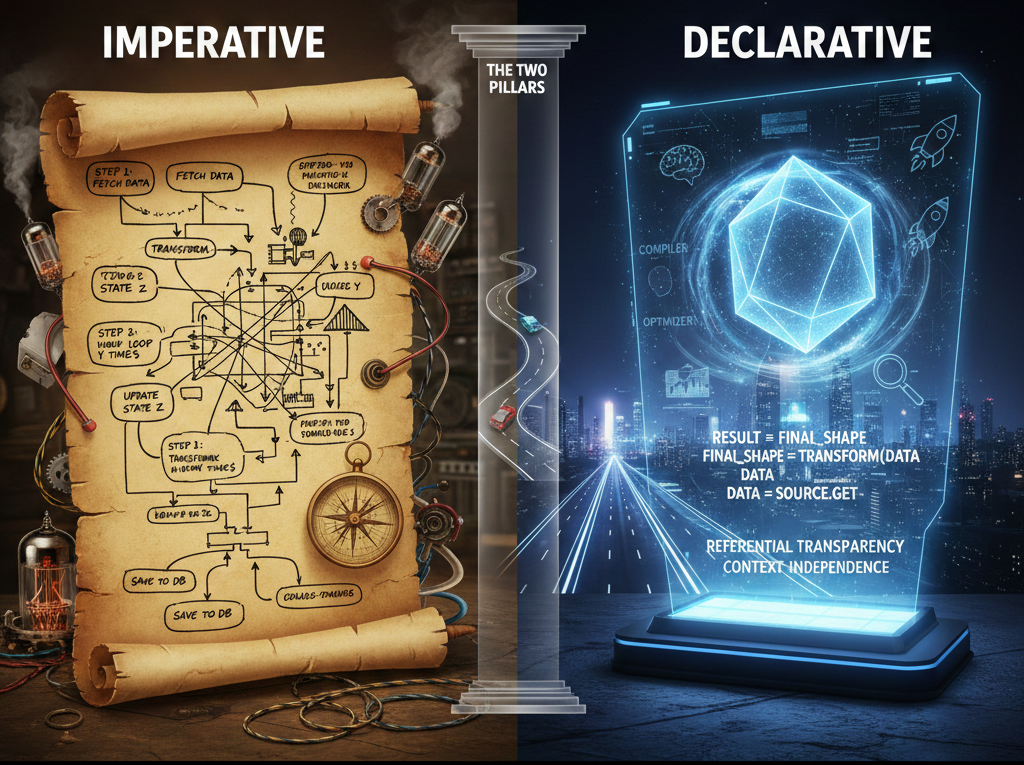

The Theoretical Power of Referential Transparency

The difference between defining what the system should achieve (declarative) and dictating the step-by-step how (imperative) rests on two pillars: Referential Transparency (a piece of code always yields the same result, like a reliable map) and Context Independence (the definition holds true regardless of the surrounding history or execution environment).

In the old way (imperative), the code is a detailed travel itinerary, tightly binding the result to every twist and turn of the machine’s state changes and hardware dance. The new way (declarative) is a constructive blueprint—a crystal-clear definition of an ultimate shape that remains constant, no matter the route. Because this blueprint only specifies the destination, not the path, the hidden engine (compiler, interpreter, or database) is given immense, almost artistic, freedom to pave the way for maximum efficiency.

The Modern Parallel: AI as the Ultimate Interface

Today, we have Generative AI. Large Language Models (LLMs) are the “ultimate declarative interface”. You don’t even need a 4GL anymore; you just need English. You tell the AI your “intent”—your “vibe”—and it synthesizes the procedural code for you.

We are, once again, standing on the precipice of “Great Hope”. We believe we’ve finally found the “Silver Bullet” that will let us program without the programmers.

But history has a sarcastic way of repeating itself. Just as the Roman Empire eventually realized that pointing at a map doesn’t account for the fact that the “wall” is being built on a swamp, enterprise IT is about to hit a very familiar, very painful wall of its own.

If you drop these smart AI assistants into your business without connecting them, you end up with more lonely towers. They might be shiny and fast, but they are isolated.

Coming Up Next…

Is it really that easy? If these tools are so powerful, why does the history of IT look like a graveyard of billion-dollar disasters?

Join me for Part 2: The “80/20 Trap” and the Catastrophe of the “Black Box,” where we’ll explore what happens when the “magic” meets the messy reality of complex business logic and why 90% of “finished” code sometimes doesn’t actually exist.